We tend to think of pilgrimage as travel to historic holy places such as Jerusalem, Rome, Mecca, Lourdes, or Santiago de Compostela. However, pilgrimages often entail a significant inner spiritual journey as well.

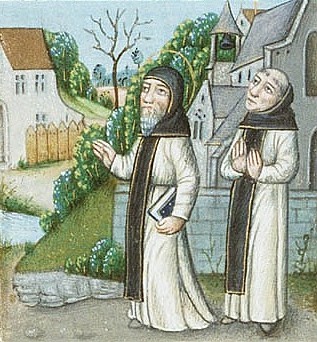

Mike and I just returned from such a pilgrimage to Iona, a small island in the Inner Hebrides off the northwest coast of Scotland. To get there requires a lengthy combination of planes, trains, buses, and ferries. Iona is where St. Columba landed in 563 CE with twelve of his most devoted monks, having left Ireland to establish a new monastic community.

It became a renowned center of learning, and its scriptorium produced highly important documents, including the Book of Kells. Between 795 and 825 massacres occurred on Iona during several Viking raids of the island and its abbey, killing the monks who, without weapons, were defenseless. Beginning in about 1200, Benedictines built the existing stone abbey on Iona, although it was abandoned after the Protestant Reformation and fell into ruin. In 1938, the Rev. George MacLeod had a vision for restoring the abbey and creating again a faith community and center for spiritual formation on the island.

For many, Iona exemplifies the ancient Celtic concept of a “thin place,” a place where the veil between heaven and earth is porous, nearly transparent, where the two worlds become almost one. One factor in its “thinness” may be the extreme beauty of the place. In Iona, as well as other places I’ve visited, I’ve been overwhelmed by the magnificence of God’s creation in a way that makes me feel God’s nearness. Another factor may be the place’s sense of sacred history. Iona certainly has this. As Bill Stone, one of our tour leaders said about the Abbey church, “These stones are soaked in prayer.”

But I realized, after warm, open-hearted interactions with the other pilgrims who were there, that the sense of heaven also comes from the Holy Spirit as it is evident in the lives of others. The lovely people I came to know created a thin place for me as they radiated the love of Christ.

Pilgrimages to thin places like Iona are a reminder to us that we are sojourners here on earth, and that the kingdom of heaven is our home. Eventually, pilgrim, as W.H. Auden wrote, “you will come to a great city that has expected your return for years.”[1]

[1] W.H. Auden, For the Time Being: A Christmas Oratorio, 1944.