Advent is a time of expectation, anticipation, and waiting. What should we do while waiting? Here is a podcast I made last year during Advent.

A lay person who strives to follow the Rule of Saint Benedict, however imperfectly.

Advent is a time of expectation, anticipation, and waiting. What should we do while waiting? Here is a podcast I made last year during Advent.

Born in Hungary, Margaret of Wessex was the daughter of the English Prince Edward in exile and his wife Agatha. Margaret became the queen of Scotland from 1070 to 1093 as the wife of Malcom III. Chroniclers depicted her as a strong, pure Christian of noble character, who had great influence over her husband, the king, and instigated religious reform in the Church in Scotland.

Queen Margaret also was known for her charitable works, serving orphans and the poor every day, before she herself ate, and washing the feet of the poor in imitation of Christ. She rose at midnight every night to attend the nighttime service of prayer. She invited the Benedictine Order to establish a monastery in Dunfermline, Fife, in 1072 and established ferries to assist pilgrims journeying across the Firth of Forth to St. Andrews, which claimed to possess bones of the saint.

She used a cave on the banks of the Tower Burn in Dunfermline as a place of devotion and prayer. Among her other deeds, Margaret also instigated the restoration of Iona Abbey in the Inner Hebrides Islands. She is also known to have interceded for the release of English exiles held in captivity during the Norman conquest of England, paying their ransoms and setting them free.

Margaret was as pious privately as she was publicly. She spent much of her time in prayer, devotional reading, and ecclesiastical embroidery. Her life is celebrated by the Church on November 16.

Prayer

O God, who called your servant Margaret to an earthly throne that she might advance your heavenly kingdom, and gave her zeal for your church and love for your people: Mercifully grant that we also may be fruitful in good works, and attain to the glorious crown of your saints; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

From the Rule

Let the Abbot exercise the utmost care and concern for delinquent brethren, for “it is not the healthy but the sick who need a physician” (Matt 9:12) . . . He ought to use every means that a wise physician would use . . .

. . . Let him imitate the loving example of the Good Shepherd who left the ninety-nine sheep in the mountains and went to look for the one sheep that had gone astray, on whose weakness He had such compassion that He deigned to place it on His own sacred shoulders in order to carry it back to the flock (Luke 15:5).

Reflection

Sending someone away for the sake of the community does not mean that the one who is banished is gone from our hearts and our prayers. Love and, when needed, care follow that one as long as they are needed.

Easier said than done, right? Often, necessary discipline is accompanied by feelings of disappointment—if not anger and disgust—toward the offender. We don’t necessarily want to think about that person again or be reminded of the offenses that led to the decision for exclusion. Our response is good riddance.

But this is not Jesus’s teaching or the guidance from Benedict. Jesus taught us to love our enemies. His examples of the prodigal son and parable of the good shepherd tell us to leave open the hope for repentance and return of the one who has grieved us.

Prayer

Merciful God, help me to love the sinner and welcome back the lost one. Amen.

Mike and I just spent three weeks in France. On the last Sunday of our vacation in France, my Cornerstone sister Judy took us to Taizé, an ecumenical monastic community in rural Burgundy, currently comprised of about 80 brothers: Catholic, Anglican, Protestant, and Orthodox men from about thirty countries around the world. The community was founded by Brother Roger Schutz in 1940 as a refuge from those escaping war.

As one website says, “the Taizé community promotes Christian unity and reconciliation through prayer, work, and hospitality,” what Br. Roger called a “parable of communion.” Although it is best known for its music, the community’s principal aim has always been to live out the Gospel in ministry to the poor and love for their neighbor.

It has become a global phenomenon, especially popular with young people. Hundreds—and on special occasions, thousands—of people flock to its services or come for week-long retreats.

Driving up to the sprawling worship building, the Church of Reconciliation, a wooden structure that has been gradually expanded through the years, I was impressed by its simplicity after seeing many grand Gothic and Romanesque churches in the region.

As bells were ringing, people quickly filed in for the ten o’clock Eucharist service.

Entering the sanctuary, I was stunned by the beauty of the place. At the top of the brightly-colored walls were simple stained-glass clerestory windows, and soft lighting and silence contributed to the sense of a sacred space. Most worshipers sat cross-legged or knelt on the carpeted floor, the white-robed monks kneeling in a wide center aisle. We sat on the steps at the side of the space. Side benches also were provided for those who needed them.

Worship roughly follows the customary format for liturgical worship and consists primarily of chants in Latin and sometimes several other languages.

Hearing hundreds of people sing the repetitious chants, most often in four-part harmony, was exceptionally beautiful. Though many are sung a capella, some are accompanied by an excellent guitarist and keyboardist. Sometimes the last note of a refrain is held as a soloist sings a verse, over the harmonic hum, then everyone joins in the repeated refrain. The scripture lessons are read in two, sometimes three, languages. At the end of the spoken prayers, worshipers sit in complete silence for about ten minutes of contemplative prayer. Because of the large number of people, the brothers and lay Eucharistic ministers bring the bread and wine to several stations throughout the space during communion.

I found the service extremely moving. The Holy Spirit was there. The German woman sitting next to me was in tears, and I fought back tears as well. It was one of the most pure worship experiences I have ever had. No sermon was given, but God spoke to me nonetheless.

From the Rule

So, brethren, we have asked the Lord who is to dwell in His tent, and we have heard His commands to anyone who would dwell there; . . . Therefore we must prepare our hearts and our bodies to do battle under the holy obedience of His commands. (RSB Prologue, Part 6)

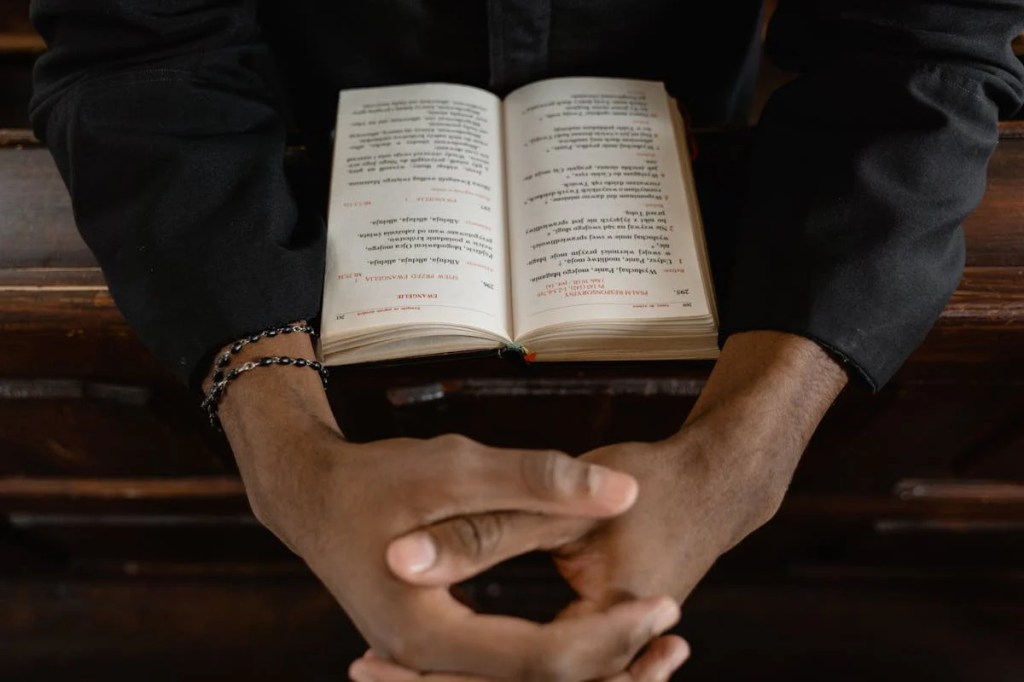

From Praying with Saint Benedict

Preparing our bodies may be easier to understand than preparing our hearts. We don’t wait until we are physically fit to begin our exercise regimen. We don’t wait until we are well before we begin taking our medicine. However, we may wait until we feel full of God’s love before we are ready to share that love with others, forgetting that in the Gospels, love is an act of obedience.

We should not wait until the warm fuzzy feeling comes before we love our neighbors as ourselves. We mistakenly operate under the assumption that it is the feeling that motivates the behavior but, in fact, it may be the behavior—the act of obedience—that nurtures the emotion.

So what do we do to prepare our hearts? First, we remember to pray, remembering that communication is essential to any relationship, including our relationship to God. Second, we gather with others in our spiritual family in order that we may encourage each other in love and good works. And finally, in obedience, we love our neighbors as ourselves. In feeding the hungry, clothing the poor, sheltering the homeless, and visiting the prisoner, we find Christ in others and discover what God’s love is all about.

Prayer

Loving God, prepare my mind for action, my body for service, and my heart to love you wholly. Give me the grace of your spirit to love others as you have loved me. Amen.

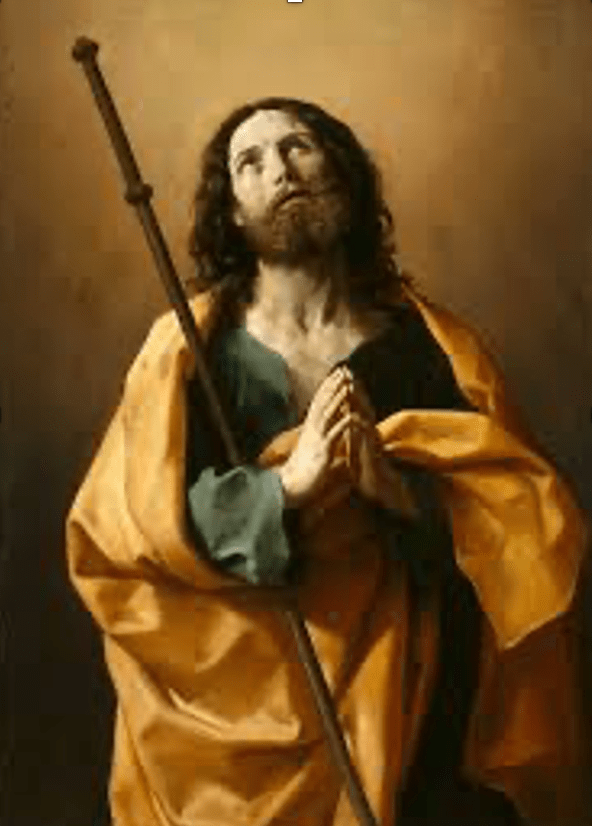

Saint James, also known as the Apostle James or James the Greater, was one of Jesus’ twelve disciples. He was the brother of John the Evangelist. As the two worked with their father mending their nets in a fishing boat on the Sea of Galilee, Jesus called them to become “fishers of men.”

The nickname Jesus gave the two brothers—the “sons of thunder”—was an apt one. When Samaritans would not welcome Jesus because he was on his way to Jerusalem (a city Samaritans hated), the disciples James and John saw this and asked, “Lord, do you want us to call down fire from heaven to consume them?” Jesus turned and rebuked them (Luke 9:54-55).

James was one of three who had the special privilege of witnessing the Transfiguration, the raising to life of the daughter of Jairus, and Jesus’ agony in Gethsemani.

To the best of our knowledge, James was the first of the apostles to be martyred. King Herod had him killed by the sword. Little else is known of his life. Tremendous devotion to him grew up around a tomb in Santiago de Compostela in Spain. How James came to be buried there was a mystery. According to legend, he had traveled to Spain in the early years of his brief ministry and met with little success, winning over only a handful of disciples.

Legend also tells us that two of his disciples, Theodore and Athanasius, accompanied him back to Jerusalem, where he was beheaded at the hands of Herod. It is believed these disciples stole his body and with it climbed into a rudderless boat. They begged God to be their pilot; the boat drifted to northern Spain, and there James was buried. Saint James is the patron saint of pilgrims and of Spain. We celebrate his memorial feast day on the 25th of July.

Prayer

Gracious God, we remember before you today your servant and apostle James, first among the twelve to suffer martyrdom for the name of Jesus Christ; and we pray that you will pour out upon the leaders of your Church that spirit of self-denying service by which alone they may have true authority among your people; through the same Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever. Amen.

Pentecost

Excerpted from A Confirmation of Faith: Chap. 8 The Holy Spirit

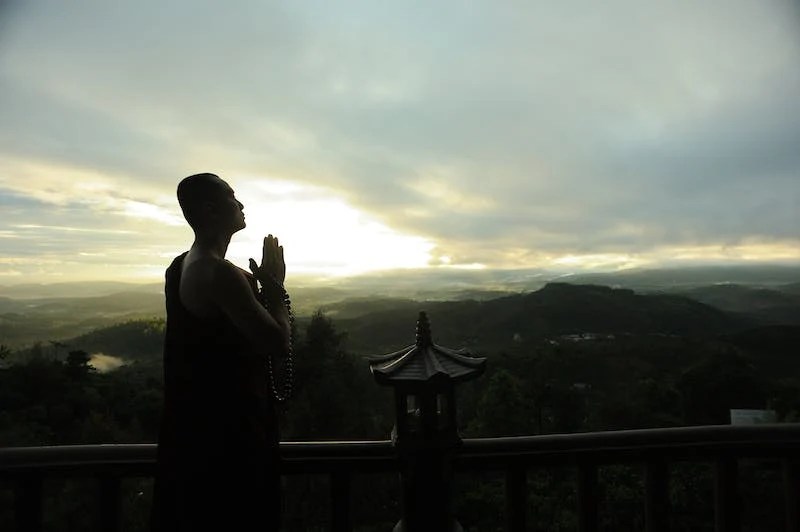

You may have experienced the Holy Spirit. You may be singing a familiar hymn in church, and you are moved by the words that suddenly have a deeper meaning than you realized previously. You are sitting by a river in a beautiful valley and are overwhelmed by the beauty of the place and the sense of God’s presence. You wake up thinking about someone in need and feel compelled to call or visit that person.

Richard Rohr describes the Holy Spirit as that aspect of God that works secretly, largely from within at the deepest levels of our desiring. It is an inner compass, a “homing device” in our soul, “an implanted desire that calls us to our foundation and our future.” Metaphors of the Holy Spirit in scripture include wind, fire, a descending dove, and flowing water.

Michael Horton emphasizes that the Holy Spirit is the presence who works within us, even to the point of indwelling us and interceding in our hearts.

In John’s gospel, Jesus comforts his disciples before his arrest and crucifixion by saying that God the Father would send an advocate in Christ’s name, the Holy Spirit, who “will teach you everything, and remind you of all that I have said to you” (John 14:26). We celebrate the gift of the Holy Spirit on Pentecost Sunday every year.

The Holy Spirit was dramatically at work in the early church. Luke and Paul make frequent reference to this member of the Trinity in their epistles. On the day of Pentecost, after the speaking in tongues and an inspiring sermon by Peter, many in the gathered crowd welcomed his message and were baptized. According to Acts, about three thousand persons were added to the followers of the Way that day. “They devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers” (Acts 2:42). Acts makes frequent reference to the Holy Spirit in the courage of the disciples to preach and heal and bear witness of the Gospel to skeptical leaders. Paul wrote to the church in Rome that it is the Holy Spirit that pours God’s love into our hearts (Rom. 5:5), intercedes for us when we don’t know how to pray (Rom. 8:26), and leads us from fear into confidence as children of God (Rom. 8:14-16).

The earliest Christians spoke of the Holy Spirit as a feminine figure. Many early Christian authors—in particular, those who had been practicing Jews—spoke of the Holy Spirit as Mother. An essential reason for this practice is the fact that the Hebrew word for Spirit, ruach, is in nearly all cases feminine. Also in Aramaic, the word for Spirit, rucha, is feminine. The first Christians, all of whom were Jews, took on this practice.

The Holy Spirit is at work in the church today. The Greek Orthodox prelate and theologian John Zizioulas maintains that the Holy Spirit is “the person of the Trinity who actually realizes in history that which we call Christ,” our Savior. Saint Augustine wrote, “what the soul is to the body of man, that the Holy Spirit is to the Body of Christ, which is the Church.” Our ability to love the stranger and see the Christ in others is a gift of the Spirit. And, as we like sheep are prone to wander, it is the Holy Spirit that intercedes on our behalf and draws us ever so gently but insistently back into fellowship with God.

From the Rule of Benedict (Chap. 67):

When brethren return from a journey, . . . let no one presume to tell another whatever he may have seen or heard outside of the monastery, because this causes very great harm.

From Praying with Saint Benedict:

A few years ago, I occasionally went to Salem, our state capital, for meetings of educators from around Oregon. I would jump in my car, check my fuel level, back out of my driveway, and hit the road. In about fifty to sixty minutes I’d be there. For the most part, it was an uneventful trip, and many times, I arrived without remembering anything about the ride.

Traveling in the sixth century was a different matter. The Roman Empire had collapsed in the West, and Europe was being overrun by barbarian tribes. Most likely, the monks traveled on foot and were likely to encounter all manner of people and circumstances. Prayers for their journey were undeniably necessary, and they returned with their heads full of the sights and smells and temptations experienced on their travel adventure. Benedict wanted to preserve the sacred, sanctuary nature of the monastery. Tales of the traveler’s experiences would not necessarily be very edifying, especially to the young monks.

Parents certainly know how to censor their conversation around their children. Benedict must have had the same concerns around his novices and younger monks. Restraint of speech involves asking yourself, Is it necessary to say this? before telling about your various adventures in the world. Would what I have to say benefit or uplift those who are listening?

Prayer

God of great wisdom, guard those who travel. Guide their paths and keep them safe. Guard also my lips when I have stories to tell, and give me the wisdom to restrain my tongue. Amen.

From the Rule: “Those who are to be received shall make a promise before all in the oratory of their stability, their reformation of life, and their obedience . . .” (RSB 58).

Reflection from Praying with Saint Benedict:

Three promises are made when novices take their vows: stability, obedience, and reformation of life. (Other translations of the Rule transcribe the original phrase conversio morum—or conversatio—as “conversion of life” or “conversion of morals.”)

In my Benedictine community, we define these three vows this way:

• Stability is the promise to remain in community, even though close relationships can create interpersonal tensions, and to stay faithful to our practice.

• Conversion of Life is a commitment to practice the ideals of scripture and the Rule to sanctify everyday living, acknowledging spiritual transformation.

• Obedience is responding with deference to the abbot and others in the community and accepting the example of Jesus to seek what is best for others.

The three promises are interrelated. Stability is an act of obedience to the community, and reformation of life empowers us to be both more stable and more obedient. In other orders, monastics also take vows of chastity and poverty, but Benedict saw these as outcomes of a conversion of life and obedience.

All of the interpretations refer to one’s manner of living. In a monastery, this change of life is indicated in the novices’ final symbolic act: putting aside their own clothes and taking on the wardrobe of the monastery.

As Michael Casey points out, conversion is a necessary starting point for the spiritual journey as well as a necessary device to bring us back on course when we have drifted away. And it is a gift of grace. We cannot bring it about through our own efforts. God calls out to us, and we respond by reorienting our lives to grow into the kind of person God created us to be. We change because we can do no other.

M. Casey, The Road to Eternal Life (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2011), 6–7.

S. Isaacson, Praying with Saint Benedict: Reflections on the Rule. (New York: Morehouse, 2021), 8-9.

From the Rule of St. Benedict (Ch. 49)

The life of a monastic should have about it at all times the character of a Lenten observance. Yet since few have the virtue for that, we therefore urge that during the actual days of Lent the community keep their lives most pure and at the same time wash away during these holy days all the negligences of other times. And this will be worthily done if we restrain ourselves from all vices and give ourselves up to prayer with tears, to reading, to compunction of heart and to abstinence. During these days, therefore, let us increase somewhat the usual burden of our service, as by private prayers and abstinence from food or drink. Thus, everyone of their own will may offer God “with joy of the Holy Spirit” (1 Thess. 1:6) something above the measure required of him.

Reflection

What should I give up for Lent? Benedict makes the point that all of our life should manifest the abstinence and restraint of a Lenten observance.

Isn’t restraining ourselves from sinful habits and giving ourselves to prayer, reading, and compunction of heart a good thing to practice year-round? What is the point of giving up chocolate or alcohol, as a token sacrifice, intending that we will take it up again the minute Lent is over? What is the point of giving up something we can do without while still being lax in our habits of prayer and study and service to others? Laura Swan wrote, “God hands us our asceticism through the normal circumstances of everyday life.” [1]

Benedict suggests that during Lent we increase the “usual burden of our service,” perhaps by praying more faithfully or volunteering for that ministry we have felt called to join, as well as restraining ourselves with greater intention from food and drink we don’t need. He further says we should do this of our own will, offering it to God with the “joy of the Holy Spirit.” In other words, Lent should be joyfully observed. We don’t do this to earn points with God, but rather out of deep gratitude for God’s grace to us.

Prayer

Gracious God, thank you for the joy of your Holy Spirit and the grace that inspires me to be intentional about all the things that are good for me and bring joy to others. Amen.

_____________________

David of Wales was a renowned preacher and missionary who founded monastic settlements and churches in Wales, Brittany, and southwest England. According to legend, he was born on a Pembrokeshire clifftop during a fierce storm in 500 CE.

Also, according to legend, he made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, from which he brought back a stone that now sits in an altar at St. David’s Cathedral, built on the site of his original monastery.

David and his monks lived a simple, austere existence. They ploughed the fields by hand, rather than using oxen. The monks refrained from eating meat or drinking beer. St. David himself consumed only leeks and water. During a battle against the Saxons, he also advised the soldiers to wear leeks in their hats so that they could easily be distinguished from their enemies. It is claimed that, because of one of those two events, the leek became a national symbol of Wales.

David was said to have performed miracles, the most famous taking place when he was preaching to a large crowd. People at the back of the gathering complained that they could not hear him. Suddenly, the ground on which he stood rose up to form a hill, allowing everyone to see and hear. Then a white dove (sent by God?) descended to rest on his shoulder.

He died on March 1, in 589, St. David’s Day, and was buried at the site of St Davids Cathedral, where his shrine was a popular place of pilgrimage throughout the Middle Ages. His last words to his followers came from a sermon he gave on the previous Sunday: ‘Be joyful, keep the faith, and do the little things that you have heard and seen me do.’ The phrase Gwnewch y pethau bychain mewn bywyd, ‘Do the little things in life,’ is still a well-known saying in Wales and good advice for us today.

Collect for St. David

Almighty God, you called your servant David to be a faithful and wise steward of your mysteries for the people of Wales. Grant that, following his purity of life and zeal for the Gospel of Christ, we may with him receive our heavenly reward. Amen.