On December 5th, the Cornerstone Community in Portland, Oregon, met to install two new members and, for continuing members, to renew their vows. This is the homily from that service:

In a few minutes, both our new members—who are taking their first vows—and continuing members—who will be renewing their vows—will pledge to work towards Stability, Obedience, and Conversion of Life with the help of our brothers and sisters.

According to Esther de Waal, the vows are not, as they might seem at first glance, about negation, restriction, and limitation.

They are saying Yes to entering into the meaning of our baptism as Christians and into the paschal mystery of suffering and dying with Christ so that we may rise again with him.[1]

Let’s talk a bit about that first vow: the promise of stability. De Waal says stability is fundamental, because it raises the whole issue of commitment and fidelity. Our customary defines stability as “the promise to remain in community, even though close relationships can create interpersonal tensions, and to stay faithful to our practice. There are three facets of stability that are relevant to our lives as monastics: stability of place, stability of practice, and stability of purpose.

Stability of place has unique salience for me. In my young adulthood, as my career was evolving, I moved around a lot. I changed churches frequently. And those changes did not always benefit my emotional or spiritual development. At some point in my mid-20s—I don’t remember exactly when—my habit of daily prayer went away. The habit of greeting God in the morning, setting aside a quiet time for prayer during the day, and saying goodnight to God, giving thanks for the blessings of the day, were no longer part of my daily routine. The religion I practiced on Sunday had little impact on my day-to-day life during the week.

So, imagine the significance for me of standing in a Cornerstone gathering in January, 2010, and pledging stability at a church where I intended to stay, with a community I loved and people I wanted to be with for the rest of my days. And I learned, in the years since then, that stability of place is a significant factor in stability of practice and stability of purpose.

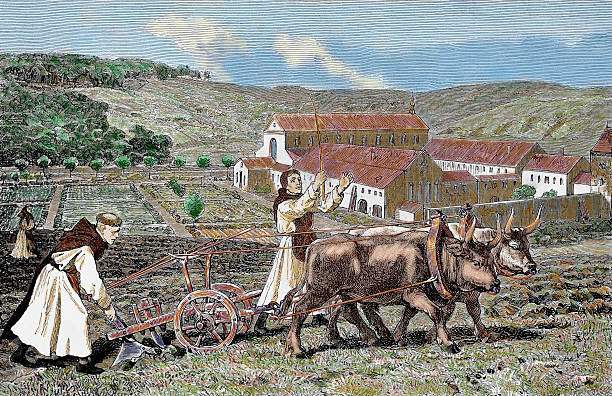

Joan Chittister has something to say about stability of place in her commentary on Benedict’s chapter on the type of monks. Responding to Benedict’s description of hermits, Sarabaites and Gyrovagues, those who chose to do their own thing or wandered from monastery to monastery, Sister Joan wrote this:

“If any paragraph in the rule dispels the popular notion of spirituality, surely this is it. Modern society has the idea that if you want to go away by yourself and ‘contemplate,’ and that if you do, you will get holy.” She continues, “It is a fascinating although misleading thought. The Rule of Benedict says that if you want to be holy, stay where you are in the human community and learn from it. Learn patience. Learn wisdom. Learn unselfishness. Learn love.”[2]

Life in community is central to our practice, even when close relationships sometimes create interpersonal tensions.

The definition in our customary also has something to say about stability as staying faithful to our practice. Reading the Rule and setting aside time every day to read a little scripture and—most of all—pray has had everything to do with my spiritual health and, I’m sure, yours as well. That practice, as Benedict describes it, includes gathering together with others for worship and participating in the sacraments. The Apostle Paul exhorted the Christians in Jerusalem to “provoke one another to love and good deeds, not neglecting to meet together, as is the habit of some, but encouraging one another, and all the more as you see the Day approaching.[3]

But stability also has to find a place in one’s heart—one’s sacred purpose. Esther de Waal makes the point that stability relates primarily to persons and not only to place. At the heart of stability there is the certitude that God is everywhere, that if we can’t find God in our present circumstances, we won’t find Him anywhere, because the kingdom of God begins within us. God is our center of gravity.

De Waal uses the analogy of a newly pregnant woman. She goes about her daily business with the only difference between her and others around her is her quiet knowledge that she is carrying a child. She carries that secret life around within her, and the mystery of this, which applies to both men and women, is that it is totally there whatever the external circumstances.

One definition of stability relates to mathematics, specifically to probability distributions that retain their integrity in spite of occasional outliers or anomalies. I don’t know about you, but my actions and behaviors certainly have their occasional outliers and anomalies. Will we fail from time to time? Most certainly. But we carry on because we have that seed within us that tells us who we are and to whom we belong.

In times of rapid social change, stability takes on particular relevance for us. Those of us who are Trinity members are entering a nervous time of transition as we think about finding a new dean. In addition, our recent national election and uncertainty about new leadership have created much anxiety in many of us. Let’s be mindful that those both within and outside our church communities will be looking to us for stability as we enter into perilous—possibly dark—times ahead in our world, remembering that darkness isn’t entirely a bad thing. It is in the darkness that one notices the light. And we are called to be that light to the world.

Stability does not imply passivity. In our mobile culture we cannot always guarantee stability of place. We have two members that live in a different country, and we have had members that have moved away because of work or family. But we can pledge to continue our practice, with God’s help, where we are planted, and to give our heart to God’s purpose, with courage and perseverance.

Paul uses the analogy of spiritual warfare. In his letter to Timothy, he says,

“Pursue righteousness, godliness, faith, love, endurance, gentleness. Fight the good fight of the faith; take hold of the eternal life to which you were called and for which you made the good confession in the presence of many witnesses.”[4]

The teacher and therapist Prentis Hemphill talks about stability of purpose and names courage as an essential element. As we look at the world around us, it is clear that we are called to be instruments of change. But, according to Hemphill, it will not happen without risking something of ourselves, perhaps by seeing ourselves honestly and stepping up when God calls us to action. “The courage we need is the courage to fail and stay,” says Hemphill. “The courage to reimagine every aspect of our social relations. . . The courage to reach for one another. The courage to be honest. The courage to ask questions. The courage to listen. The courage to feel uncomfortable. The courage to be a part of the circle, to be fed by and to feed. The courage to surrender . . . The courage to love and be loved.”

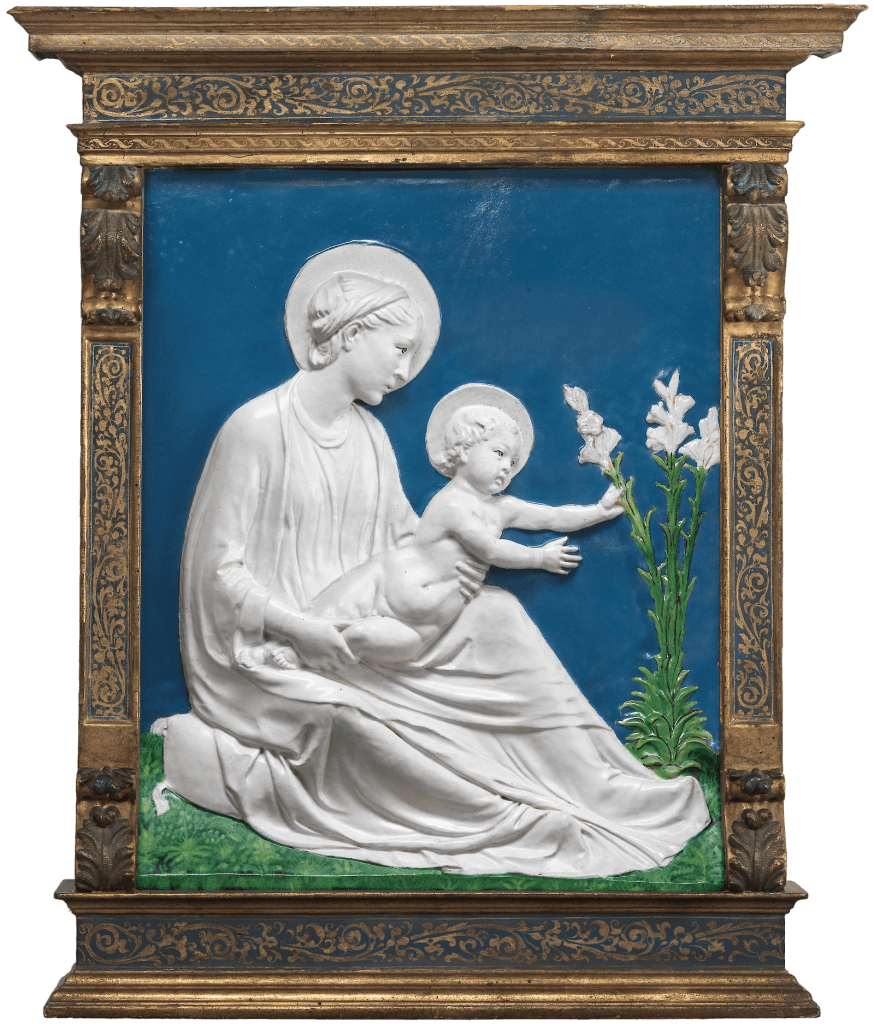

Until Sunday night, I wasn’t sure how I wanted to end this homily. Those of you who attended Trinity’s Advent Lessons & Carols heard, with me, this powerful poem by Marie Howe, inspired by the angel’s annunciation to Mary. It moved me because it instantly made me remember my own calling when I joined this community:

Annunciation

by Marie Howe

Even if I don’t see it again—nor ever feel it

I know it is—and that if once it hailed me

it ever does—

And so it is myself I want to turn in that direction

not as towards a place, but it was a tilting

within myself,

as one turns a mirror to flash the light to where

it isn’t—I was blinded like that—and swam

in what shone at me

only able to endure it by being no one and so

specifically myself I thought I’d die

from being loved like that.

So, brothers and sisters in Christ, carry on. Fight the good fight. Be the light that the world needs.

[1] Esther de Waal, Seeking God. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1984), 55.

[2] Joan Chittister, The Rule of Benedict: Insight for the Ages. (New York: Crossroad, 1992), 33.

[3] Heb. 10:24-25

[4] 1 Tim. 6:11-12