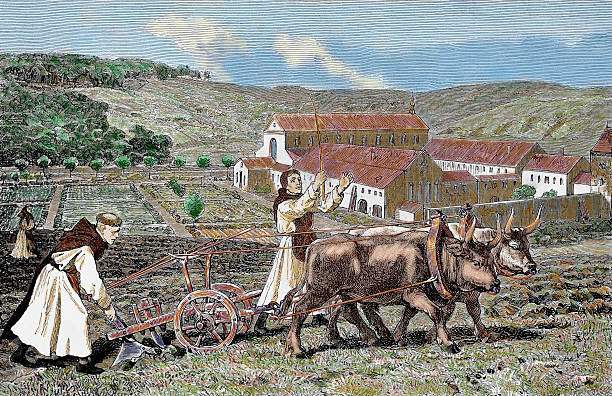

In Chapter 48 of his Rule for Monasteries, Benedict wrote: “Idleness is the enemy of the soul. Therefore, the brothers and sisters should be occupied at certain times in manual labor, and again at fixed hours in sacred reading….”

Ora et labora—prayer and labor—was Benedict’s motto. In the Rule, Benedict extols the virtues of physical labor as a cure for idleness, “the enemy of the soul.” I certainly find satisfaction with a physical job done well, whether it’s mowing the lawn or organizing my sock drawer. Of course, in Benedict’s world, prayer also counts as important work—the opus dei, or work of God.

However, looking closer at the workday he recommends, the work requirement is hardly onerous. After the morning office and breakfast, the monks engaged in physical tasks until about nine or nine thirty, at which time they probably did Terce, the mid-morning service of prayer. Then in late morning, the monks read. (I like that reading counted as work.) After lunch, the monks took a nap, resting (or sometimes reading) until the afternoon service of None. Then they completed their work until Vespers at about five or six o’clock.

This schedule amounted to only about four or five hours of physical work, which was thoughtfully scheduled to avoid the heat of midday.

And, of course, the most important work was prayer, the work of God (opus dei). Prayer is the priority in the monastery, as indicated by the seven offices throughout the day.

Ora et labora is another example of balance, Benedict’s principle of how monastery life—or any spiritual life, for that matter—should be lived.

________________________

From Praying with Saint Benedict (New York: Morehouse Publishing, 2021), 29-30.