This is a video of a presentation I gave to a Catechesis class at Trinity Episcopal Cathedral in Portland, Oregon, on Benedictine prayer practice (March 8, 2023). Bill Bard was the session leader.

Faith and Reason

Today the Church celebrates Saint Anselm, an 11th century Benedictine monk who eventually became an abbot and, finally, Archbishop of Canterbury. He is best known as a philosopher and scholar who strove to apply reason to explore the mysteries of faith. His brilliant writing is still much respected today and influences much of current theology.

It was Anselm who defined theology as “faith seeking understanding.” In 1077, he wrote the Monologion (“Monologue”) at the request of his fellow monks, a theological treatise that attempted to demonstrate the existence and nature of God by appeal to reason alone rather than by the usual reference to traditional authorities. In a later work, Cur Deus homo? (“Why Did God Become Man?”), he also explicated the satisfaction theory of atonement or redemption.

Appointed by William II (Rufus) as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1093, he reluctantly accepted the position, but used his position to fight for reform in the English church, resulting in a contentious relationship with both Rufus and his successor, Henry I.

St. Anselm stands as a demonstration of the possibility that reason and intellect do not stand in opposition to faith. Anselm’s faith did not come strictly from the church’s dogma; his own inquisitive mind found reason to believe in the existence of God and Christ’s role in our salvation. As a Benedictine, he upheld the virtues of humility, stability, and conversion of life. Although known to be a gentle, patient man and lover of peace, he did not back away from conflict when principles were at stake.

Prayer

Steadfast God, help us to grow into persons of faith like Anselm, practicing reason, compassion, and courage as we grow more into the likeness of Christ himself. Amen.

Taking Up the Cross

This year, for a choral evensong service on Passion Sunday, the Trinity Cathedral choir and organ performed a musical setting of Via Crucis (Stations of the Cross) by Franz Liszt. One piece stood out to me: the fifth station, Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus carry the Cross. I thought about what it must mean to carry Jesus’ cross.

Cyrene was a city in eastern Libya, an area of North Africa that had become a Roman colony. How did Simon happen to be on a Jerusalem street just as the prisoner and soldiers were on their way to Golgotha? Was Simon drawn to the scene by the crowd that had gathered? Was he a secret follower of Jesus who wanted to witness what was happening to him?

He was probably a person of color. He may have been Jewish. Cyrene had a sizable Jewish population, some of whom came to Jerusalem once a year for Passover.

All three synoptic gospels tell the story. Simon was a passer-by at the scene, coming into Jerusalem “from the country” when he was compelled by the soldiers to carry Jesus’ cross. Jesus previously had been beaten, may have been bleeding, had fallen once, and was probably very weak. We don’t know how long he carried the cross, probably all the way to Golgotha. Scripture makes no mention of Simon of Cyrene after the crucifixion. According to tradition, he went to Egypt to spread the Gospel and was martyred in 100 CE by being cut in half with a saw.

Earlier in Luke’s account of Jesus’ life, Jesus foretells of his crucifixion and resurrection in conversation with his disciples. Then he says, “If any wish to come after me, let them deny themselves and take up their cross daily and follow me” (Luke 9:23).

What does it mean to “take up one’s cross daily?” Jesus gives us a pretty good idea in a parable he told his followers in Matthew 25. When the righteous asked the king, “Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food or thirsty and gave you something to drink? And when were you a stranger that we welcomed in, or naked and we clothed you? And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’

The king answered them, “Just as you did it to one of the least of my brothers and sisters, you did it to me.”

We are the hands and feet of Christ in the world (or, in Simon’s case, possibly the shoulders). We shoulder the cross when we volunteer in a food bank or homeless shelter, visit someone in prison, sit at the bedside of a family member who has not always treated us kindly, listen compassionately to a friend talk about abuse even as it resurrects painful memories of our own, speak out in a public meeting about an injustice that has happened in our community.

The cross is the symbol of our faith, which suggests that taking up the cross also means, as Peter said in his first epistle, to “Be ready at any time to give a quiet and reverent answer to anyone who wants a reason for the hope that you have within you.” (1 Pet. 3:15-16).

In other words, we take up Jesus’ cross when we self-sacrificially become Christ to others, in word and deed.

Prayer

Almighty God, whose most dear Son went not up to joy but first he suffered pain, and entered not into glory before he was crucified: Mercifully grant that we, walking in the way of the Cross, may find it none other than the way of life and peace; through Jesus Christ your Son our Lord.

Wondrous Reading

From Praying with Saint Benedict:

Maryanne Wolf ’s remarkable book Proust and the Squid begins with these words:

We were never born to read. Human beings invented reading only a few thousand years ago. And with this invention, we rearranged the very organization of our brain, which in turn expanded the ways we were able to think, which altered the intellectual evolution of our species. Reading is one of the single most remarkable inventions in history . . .[1]

In an age of wide-spread illiteracy, reading was an invention that Benedict embraced, and he required it of all his monks (RSB Ch. 48). Benedict was a well-educated man who, I suspect, believed that reading was as important to a brother’s spiritual development as it was to his intellectual development.

Only when someone would not or could not read would they be assigned another more menial task or a craft. In his epilogue to the Rule (Ch. 73), he challenges the reader to study the “divinely inspired books” of the Old and New Testaments and the extensive writings of the early fathers.

I think about the impact of contemporary Christian writers and thinkers on my spiritual formation. After reading Esther de Waal’s Seeking Life [2], I will never look at baptism or the Easter Vigil the same way again. Michael Casey [3] taught me an appreciation for the “grace of discontinuity,” a sometimes disruptive change in life circumstances that leads to a spiritual transformation. We read to understand more about the “mystery of Christ.”

Prayer

Wise and loving God, thank you for the enlightened men and women who have shared their insights through writing. Sustain in me a desire to learn and apply their wisdom. Amen.

____________________________

1. Maryanne Wolf, Proust and the Squid (New York: HarperCollins, 2007), 3.

2. Esther de Waal, Seeking Life (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2009).

3. Michael Casey, Grace: On the Journey to God (Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2018).

A Silent Meal

Monastic meals nourish the body and soul. In Chapter 38 of his Rule for Monasteries, Benedict describes what should happen during the main meal of the day. “The meals of the brethren should not be without reading. Nor should the reader be anyone who happens to take up the book; but there should be a reader for the whole week . . . And let absolute silence be kept at table, so that no whispering may be heard nor any voice except the reader’s. As to the things they need while they eat and drink, let the brethren pass them to one another so that no one need ask for anything.”

From Praying with Saint Benedict, my reflection:

At the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, following the Rule, no conversation takes place at the meals. At the midday meal on my first visit, after two chanted prayers, monks and guests sat to hear the first reading, a short passage from Exodus. Then, as the meal was served, the designated reader for the week began the second reading from a devotional book with chapters on compassion, forgiveness, anger, and humility. On other visits, the reader has read from biographies of modern saints. At the end of the meal, the reader read a short passage from the lives of the early fathers. Lunch ended with a chanted thanksgiving and a sung prayer to St. Benedict.

[Benedict’s] chapter on the meal readings underscores several principles of The Rule. The first principle follows Benedict’s teaching on restraint of speech: during meals, complete silence. The introvert in me found great relief in not having to make dinner table conversation with the strangers on either side of me. I was free just to sit in silence and listen.

The second principle is humility; the reader asks for prayer to shield him from “the spirit of vanity” and waits to take his meal with the kitchen workers and servers after others have left. A third theme addresses mutual obedience: the brothers being sensitive enough to one another’s needs as they eat and drink, so that no one needs to ask for anything. Mealtime, it seems, is a perfect time to practice holy silence, humility, and service.

Patient God, help me in every moment of my life, even during meals, to be obedient to you, looking for opportunities to listen and serve with humility.

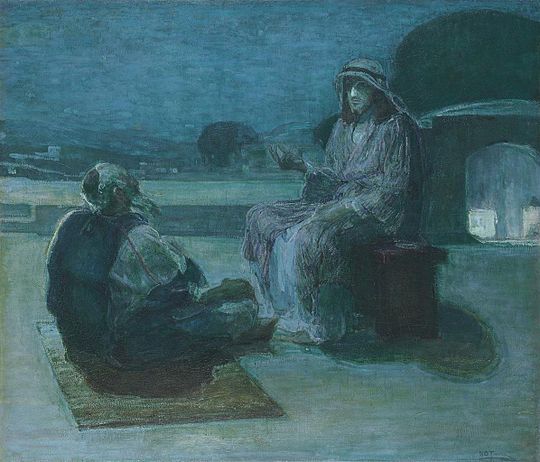

Born from Above

The Gospel reading on Sunday for the second Sunday of Lent was taken from John 3, where Jesus tells Nicodemus, “No one can see the kingdom of God without being born from above.” When Nicodemus doesn’t understand, Jesus elaborates: “What is born of the flesh is flesh, and what is born of the Spirit is spirit. Do not be astonished that I said to you, ‘You must be born from above.’”[1]

Jesus then compared the Spirit to the wind. It blows where it chooses, and we don’t know where it comes from or where it will end up.

When Nicodemus, understandably mystified by Jesus’ talk about being “born from above” and “born of the Spirit,” responds by asking, “How can these things be?” Jesus answers by comparing himself, the Son of Man, to the bronze serpent Moses put on a high pole. Anyone who was bitten by a snake could lift their eyes to look upon Moses’ bronze serpent and they would live. In other words, Jesus was saying, Look to me and I can give you eternal life, a life born of the Spirit.

Moments in our life when we have transcendent encounters with God can give us a “born from above” experience. My first was as a young boy having an honest, soul-wrenching conversation with Jesus in my bed one night. I immediately was enveloped with an incredible sense of God’s presence and love. Other encounters with God followed throughout my life, some powerful enough to shake up my life a bit and put me on a different spiritual path.

About twelve years ago I heard Elaine Harris speak about the Cornerstone Community and recognized immediately that the Holy Spirit was leading me in a new direction. It was a transformational experience that led me to becoming a Benedictine and adopt an ancient rule of life. Little did I realize then where the wind of the Spirit would take me. My life hasn’t been the same since.

Being born from above is not the destination of our spiritual journey; it is the beginning.

[1] John 3:1-17

Lent as Life

Benedict looked at Lent as a chance for a little spiritual house cleaning and an opportunity for personal growth. In chapter 49 of his Rule, he maintained that our lives ought always to have the character of a Lenten observance: that is, devoted to prayer, restraint in what we eat and drink, avoiding other vices, and “compunction of heart” (or the moral scruples that prevent you from doing something bad and acknowledging it if you have).

Realizing that few of his monks had the discipline and self-restraint for doing that as consistently as they should, Lent was a time for the brethren to “keep their lives most pure and at the same time wash away . . . all the negligences of other times.”

Lent was also a time for study. At the beginning of Lent, the abbot gave a book to each monk that they were instructed to “read straight through from the beginning.” In an age of wide-spread illiteracy, reading was a practice that Benedict embraced, and studying the scriptures was something he required of all his monks.

Most of all, according to Benedict, every act given to God during Lent should be offered “with joy of the Holy Spirit.” No long faces or martyr-like behavior during this holy season.

What should we give up during Lent? Michael Casey writes about compensatory attachments. When God is overlooked in one’s life, people often attempt to build their character around alternatives such as power, possessions, pleasure, or privilege [1]. Laura Swan states that the primary goal for the spiritual journey is detachment from these things, which leads to interior freedom. She writes, “Our goal is a life of abundant simplicity.” [2]

Isn’t devoting ourselves to prayer, reading, and giving up unhealthy behaviors a good thing to practice year-round? We don’t do this to earn points with God, but rather out of deep gratitude for God’s grace to us and obedience to a better way of life.

Prayer

Gracious God, thank you for the joy of your Holy Spirit and the grace that inspires me to resist harmful attachments and embrace those things that are good for me and bring joy to others. Amen.

St. Valentine

Confusion exists about who St. Valentine was because there have been about a dozen St. Valentines, plus a pope named Valentine. “Valentinus” was a popular name between the second and eighth centuries (meaning worthy, strong, powerful), and several martyrs over the centuries have carried this name.

The Valentine we celebrate on February 14th actually may be two of these Valentines, one being a real person who died around 270 C.E. and who Pope Gelasius I, in 496 C.E., referred to as a martyr, his acts as “being known only to God.” The other possibility is that Valentine was a priest, beheaded near Rome by the emperor Claudius II for helping Christian couples wed (thus allowing the young groom to escape conscription into the Roman army).

He has become the patron saint of many things. People call on him to watch over young lovers, but also to intervene with epileptics, beekeepers, travelers, and those who faint or have the plague. Appropriately, he’s also the patron saint of engaged couples and happy marriages.

In his Rule, Benedict never addresses romantic love, but in the prologue to the Rule, he wrote that, as we advance in faith, our hearts expand and “we run the way of God’s commandments with unspeakable sweetness of love.” In his chapter on the tools of good works, he enjoins his monks to love their enemies and show mutual obedience to each other in love. Love permeates Benedict’s instruction on leadership and discipline. Most of all, he instructs his monks to “prefer nothing to the love of Christ.”

He brought me to the banqueting house, and his intention toward me was love. (Song of Songs 2:4)

Humility

Probably the most difficult challenge for focused, self-disciplined, achievement-oriented people on their path to God’s kingdom is giving up control of our own ambitions in order to take up our cross and follow Christ. However, our own will often stands in the way of God’s will. Proverbs 16 tells us that sometimes there is a way that seems to us to be right, “but in the end it is the way to death,” and Christ himself taught “For all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted” (Luke 14:11).

In his Rule, Benedict states, “The first step of humility…is that we keep the reverence of God always before our eyes” (RSB 7). Michael Casey points out that those who have truly encountered God are filled with a sense of wonder at the mystery and, simultaneously, confounded by a sense of their own insignificance.

He continues, “This sense of littleness is what opens us up to be filled with the gifts of God, a God who looks with favor on the humility of God’s servants. Humility is not primarily a social virtue, the opposite of arrogance. It is the necessary consequence that follows an encounter with the loving holiness of God. After that it doesn’t matter much what status others assign to us.”[1]

Benedict’s chapter on humility is the longest and—Esther DeWaal argues—the most crucial of the chapters in the Rule. [2] And I think her claim makes sense. It is humility that enables us to submit to those in authority, listen with “the ear of the heart,” offer hospitality, take our turn in the kitchen, become a servant leader, restrain our speech, tend the sick and the elderly, pray.

The derivation of the word humility is from the Latin humus, the ground or earth. In DeWaal’s words, it means “to be earthed, centered, grounded.” Laura Swan describes it as becoming very real, moving toward our true self made in the image and likeness of Christ. [3] It is a state of being that should appeal to all of us.

- Michael Casey, Balaam’s Donkey: Random Ruminations for Every Day of the Year. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2019).

- Esther DeWaal, A Life-giving Way: A Commentary on the Rule of St. Benedict. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1995), 57.

- Laura Swan, Engaging Benedict: What the Rule Can Teach Us Today. (Notre Dame, IN: Ave Maria Press, 2005), 72.

Leadership

Today we remember the powerful leadership of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the enormous role he played in moving ahead the cause of racial justice. According to researchers at Harvard Business School, King exemplified not just one, but two types of vital organizational leadership.[1] First, he articulated a clear vision, set goals and established high expectations. Second, he was an example of servant leadership. He did not ask his followers to do anything he was not willing to do, including putting his life on the line for the cause.

In the 6th century, Benedict was ahead of his time in regard to understanding effective leadership. He delegated authority widely—to his prior, his deans, the cellarer, and the porter—and he listened—not just to his leadership team, but to the whole community. In chapter 3 of the Rule he states: “Whenever any important business has to be done in the monastery, let the Abbot call together the whole community and state the matter to be acted upon. Then, having heard the brethren’s advice, let him turn the matter over in his own mind and do what he shall judge to be most expedient . . .”. It is not just from the wise older men that he solicits advice, but from the young monks as well. “The reason we have said that all should be called for counsel is that the Lord often reveals to the younger what is best.”

Twenty-first-century books on leadership would not be too much different in their advice to readers. Among the eight essential leadership skills identified by Lauren Landry [2] is receiving and implementing feedback. In a survey by the American Management Association, more than a third of senior managers, executives, and employees said they “hardly ever” know what’s going on in their organizations. Asking for feedback from your team, says Landry, can not only help you grow as a leader, but build trust among your colleagues.

What stands out in Chapter 3 of Benedict’s Rule—in contrast to more authoritarian monastic rules—is the principle of humility, as modeled by the abbot in the way he leads. His leadership style is not an autocratic one and respects the wisdom of others in the community.

Prayer

Gracious God, give me the wisdom to seek council when I am making decisions that affect others and the humility to honor and support the decisions of those who lead me. May listening, love, and mutual obedience be present in our life together. Amen.

______________________________

- “Martin Luther King, Jr.: A leader to inspire businesses.” W. P. Carey News, Arizona State University, 1-17-2022. https://news.wpcarey.asu.edu/20220117-martin-luther-king-jr-leader-inspire-businesses

- Lauren Landry, ”8 Essential Leadership Communication Skills”. Harvard Business School Online, 11-14-2019.https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/leadership-communication